This blog is the result of the first complete investigation and report of the most infamous crimes in the West Palm Beach pioneer era. Although frequently mentioned, most of the information written about the Richard Hone case in newspapers or on the Internet is incomplete, and in some cases, wrong. Every available issue of pioneer-era newspapers (The Tropical Sun and the Miami Metropolis) were researched, along with probate records, baptismal and marriage records, land transactions, and maps.

***

A storm is raging along the shores of Lake Worth, an unusually violent Fall thunderstorm. Richard Hone, a 44-year-old Englishmen and naturalized citizen, sat in his country estate home three miles south of West Palm Beach, composing a letter to one of his sisters in England. Nearby sat Hone’s wife Mary, reading by lamp in the dark, dusky evening. Among the fits of light and cracks of thunder, a figure lurks outside near the window. The muzzle of a rifle bursts through the window screen; a shot is fired, hitting Hone. He grabs his head and yells “MY GOD, I AM SHOT!” It was the last words he would ever speak.

***

Richard Hone was born in 1859 to Harry and Lucinda Clarke Hone in Stoke Orchard, Gloucestershire County, England, the youngest of nine children. Hone’s father had amassed a 640-acre estate in Stoke Orchard, about two hours northwest of London. Richard Hone last appears with the family on the 1881 census, living with his mother Lucinda and siblings on the estate. With so many older brothers and sisters, little of the estate would be left to Richard. He decided to try his luck in America and arrived in New York November 20, 1894, and made his way to California.

Not finding his fortune in California, Hone arrived in the-then Dade County, Florida, which encompassed what is today Dade, Broward, Palm Beach and Martin Counties. On February 9, 1895, Hone bought 20 acres of land for $1,000 from Colonel John Huntington Jones and his wife Elizabeth Ross Jones. They were Rhode Islanders who owned much land in the West Palm Beach area. They were not related to Mary Jones, as has been said in other accounts. James Wood Davidson, a noted scholar and author from South Carolina, had acquired 108 acres along the shores of Lake Worth in 1885 through the Homestead Act. Davidson sold off the track in pieces, and Hone was now the owner of 20 of those acres, ready to start his farming enterprise.

Hone contracted with well-known pioneer-builder and architect Charles C. Haight for a house. “The building will be two stories high, with wide porches all around it, an ornament along the Lake. About the middle of July, Mr. Hone will leave for England, but will soon return with the lady who will preside over this new home.” (The Tropical Sun, May 23, 1895). Hone sailed back to England to marry a woman from his hometown, Mary Jones, 34, the daughter of Henry Yates Jones and Elizabeth Buckle Jones. The Jones were also farmers, owning a 320-acre estate. Richard and Mary married August 20, 1895, in Gloucestershire and sailed immediately from Southhampton, England, arriving in New York August 31, 1895. From there they would take the train to West Palm Beach to begin their wedded life.

Hone went into the pineapple farming business, which was most lucrative for early West Palm Beach farmers. Local plantation owners included J.W. Comstock, George Matthams, James N. Parker, George Swift, and Nellie Clow, who planted the pineapple “slips” in the sandy soils in which they thrived. Fresh pineapple was a summer delicacy that could be shipped quickly north on the train and commanded high prices in northern city markets. Hone raised the popular varieties of the day including Natal Queen and Red Spanish. He built wood lathe shades over the three acres of fields he had in cultivation to keep the sun from burning the fruit.

In March 1897, a baby girl was born to the Hones, but her life was short. Two more children were to follow; Edmond in 1899, and Robert in 1900, but they too were to meet the same cruel fate as the little girl. The Hones were a childless family.

The Hones became American citizens May, 1897 at the Dade County courthouse in Juno, Florida “Richard Hone passed through town a few days ago on his way to Juno where he went to take out his final naturalization papers. In the future Mr. Hone will fly the American flag over his ‘Lake Shore’ place.” (The Tropical Sun, May 27, 1897).

As the years went on, Hone continued with raising pineapples and vegetables as the land would support. He is listed as visiting England in 1897 as a returning citizen, but it is not known if Mary also accompanied him on the trip. Hone was a popular and respected figure around town, and the Tropical Sun staff were most appreciative of his generous nature: “This office is under many obligations to Richard Hone, whose gentlemanly features, accompanied by a sack of fancy pines, put in an appearance just before we were going to press.” (The Tropical Sun, June 10, 1897).

Monday, October 20, 1902 was a stormy evening in South Florida. The Hones had finished supper, and were busy with reading and correspondence. The storm raging outside had come in off the ocean. As the shot rang out and hit Richard Hone, he arose and quickly stumbled backward, falling in the hallway. His wife put a pillow under his head, but she knew there was little she could do for her dying husband.

Mary ran to the nearest neighbor, James Willis Comstock, who lived a few hundred yards to the southwest of the Hone property. He heard her screams, and she told of what had happened at the house. Comstock put out the lamp in his house, grabbed his revolver, locked the door and the two hurried back to the Hone house among the claps of thunder.

When reaching the Hone house, Comstock saw that Hone was dead, a pool of blood beside the body. It was an hour walk to town to find the sheriff, and another squall line was about to hit with sheets of pouring rain. Comstock could not leave Mary by herself, so he thought to bring her to the next neighbor to the south, pineapple grower James Hunter and wife Gertrude.

They went down the trail by lantern, passing Comstock’s house. Comstock noticed that his front door was now open, and that a rifle was resting against the door. The screen door had been propped open with a pair of shoes. Someone was inside the house. He urged Mary to stay back while he went inside, but instead she rushed to the porch. Comstock went to grab the rifle from the door, and out of the darkness he was tackled from behind. A fight ensued over the rifle, with both men struggling to gain possession. Mary took part too, but was quickly thrown aside by the assailant. The scuffle knocked over the lantern, making it difficult to see the assailant, but the lightning flashes revealed him to be African-American. Comstock went for his revolver, lost his grip on the rifle, and fell backward. The assailant kicked the revolver away. Comstock expected to be shot in cold blood like Hone, but instead the assailant fled west with the rifle through the sand pines and palmettos.

Comstock found his revolver, and Mary and he walked down the trail to the Hunter home. Another neighbor, Mr. Carlson, joined the group. All walked back to the Hone house, and stayed there the rest of the night as the monsoon rains returned.

At daybreak, Mr. Comstock went to West Palm Beach and found Deputy Sheriff Noah Jones. A posse of men armed with Winchester rifles went south down the lake by boat and on the bicycle trail. As was the custom of the time, the designated coroner, attorney Hutson B. Saunders, formed a jury to examine the body and crime scene so the cause and manner of death could be investigated. Â Coroner Saunders swore in his jury – J.C. Harris, William Heim, C.W. Schmid, Bernard M. Potter, George Zapf and Wilhelm Weybrecht. Dr. Henry C. Hood examined the body and found that the bullet had penetrated the right arm, entered the chest and had probably pierced the heart. Dr. Hood extracted the bullet and found it to be a .32 caliber rifle ball. The jury examined the scene and the evidence and proclaimed the cause of death was gunshot, and the manner was murder by unknown assailant.

Deputies assembled at the Comstock house to examine the crime scene there. The deputies could see the bare footprints of the assailant where he had the scuffle with Mr. Comstock. The small trail through the palmetto scrub led to the county road (where Dixie Highway is today) and on to “Potter’s Station” on the Florida East Coast Railway. Although not described in detail, it was probably a loading dock where farmers could bring produce for shipping north. The officers concluded that the assailant had headed north or south on the train tracks.

On walking back to the house, the deputies found the assailant’s cap. They also examined Mr. Comstock’s door, which showed it had been broken with the muzzle of a rifle, which left a clear impression on the door.

The shoes left behind were particularly interesting. They were a brand of shoe called “Walkover” and appeared to be new (the company was founded in 1758 and is still in business). The man who sold shoes at Anthony’s Store stated that only 3 or 4 pair had been sold in the last week. Further inquiry into the shoes showed that an African-American man, William Melton, had reported his new shoes stolen to the police on Monday morning. This would later provide an important clue linking the murderer to the crime scene.

Richard Hone’s funeral was attended by many West Palm Beach residents. The Reverend S. D. Paine of the Union Congregational Church conducted the funeral services at the Hone house. The body was then transported to Lakeside Cemetery via boat for burial, which did not take place until 5:30 in the evening, when dusk had set in. A few months before his death, Hone donated $5.00 for the improvement of Lakeside Cemetery – little did he know he would be so soon among its residents. “The scene at the grave was weird and impressive, in the extreme. A few flickering lanterns cast a fitful glare on the friends gathered around the open grave, while a solemn stillness reigned, save for the voice of the officiating minster who performed the sad last rites.” (The Tropical Sun, October 24, 1902). Marion E. Gruber, L. Marvin, George Wellington, George C. Currie, and James J. Hunter served as pall bearers. Following the services, Mary Hone stayed with the Wellington family in town, fellow Englishmen who could offer her solace in her time of need.

The small town of West Palm Beach was in shock. The reward money quickly piled up, with W.P. Hatchett pledging $500 for “For the arrest and delivery to me, in the woods, with satisfactory proof of guilt of the murdered of Mr. Richard Hone.”

The investigation as to the identity of the assailant turned quickly to men who had worked on the Hone plantation. Hone often employed laborers who would help him tend the pineapples, which is a labor-intensive crop, especially during the summer harvest months. In the Fall, new plants would be set so they could begin their two-year growth cycle to bear fruit. One person questioned soon after the crime was Billy Kelly, who had worked for Hone the Friday before the murder and did not show up for work Monday. Kelly was questioned a few days after the murder, arrested, and jailed in Miami. Recall that Mr. Melton’s new Walkover shoes were stolen; Melton’s razor was also taken in that burglary. Another burglary was committed nearby Melton’s at C.S. Archer’s house, where a rifle, bicycle, bicycle pump and bedspread were taken. A search at Kelly’s home turned up the razor and the other stolen items, except the shoes and rifle. This evidence clearly tied Kelly to the shoes found at the crime scene.

A boy walking on the scrub trail to Potter’s Station found the rifle November 22, about a month after the murder. He gave it to an adult who then turned in the rifle to a deputy sheriff. The sheriff took the rifle to Hatchett’s hardware store in town where the rifle was identified as one an African-American man had brought in looking for ammunition to fit the rifle. Mr. Comstock too was able to identify the rifle. It was no ordinary weapon, but an 1894 Winchester rifle. The original owner of the weapon, Joseph Borman, purchased the rifle in Palm Beach in 1894 at the Brelsford Store when it was located where the Flagler Museum is today. There were only three such guns sold on the lake. Mr. Borman had loaned the rifle to Mr. Archer when it was stolen by Mr. Kelly for use in the crime.

William Kelly’s trial for murder was on the Spring circuit court docket in Miami with Judge Minor S. Jones presiding; Kelly’s case would draw the most attention. Two attorneys were appointed by the judge to represent Kelly – Mitchell D. Price and H.F. Atkinson. Judge Beggs was the state attorney, assisted by H.B. Saunders, who had served as coroner in the original inquiry. The trial took place February 18, 1903 and lasted one day. “The evidence in the case was all circumstantial, but the presentation had procured a whole chain, and link by link it was fastened together until it had bound the prisoner in the hopeless fetters.” (The Miami Metropolis, February 20, 1903).

By 7:30 PM, the judge had turned the case over to the jury. The jury returned a guilty verdict at 9:00 PM, with sentence being death by hanging. The case was somewhat novel in that it only involved circumstantial evidence – no one could identify Kelly as the assailant as a direct witness. “The case was perhaps of the clearest and strongest ones, of only circumstantial evidence, ever tried in this state.” (The Miami Metropolis, February 27, 1903). There was an attempt by Kelly’s attorneys to be granted a new trial based on how the jury delivered the verdict. Judge Jones had them correct the verdict and the request for a new trial was denied.

While awaiting execution in the county jail, Kelly confessed his crime to Sheriff Frohock. Kelly believed that Hone kept large amounts of cash in the house. Kelly had practiced firing the rifle, and threw the spent shells between the two buildings where he lived. Kelly had first stalked Hone on Sunday night before the murder. He returned Monday and proceeded to kill Hone. After he fired the shot, Kelly hid behind an oleander bush as Mary ran from the house toward Comstock’s house. Kelly then entered the Hone house, looked for the money, and found none. He gazed upon the lifeless body of Hone as it lay in the hallway. Kelly was asked why he did not shoot Mary as well – he explained that his feeling of revulsion was so strong after killing Hone that he could not shoot Mary; his thoughts only went to finding money and escape.

He sat on the porch, thinking about his escape when he saw Mary and Mr. Comstock walking toward the house. He hid again behind the oleander. As they entered the house, he crept to the window and watched as Mr. Comstock examined Hone’s body. Kelly then proceeded to Comstock’s house where he broke the door with the rifle. Kelly said “I killed a man, and I want to give my life for his – he was a good man too.”(TheMiami Metropolis, March 27, 1903)

Friday, April 10, 1903 would be William Kelly’s last day. It was now time to pay society for the crime committed. Kelly was taken to the gallows in an automobile, as the headline in the Tropical Sun proclaimed, a novelty in 1903. Kelly was hung with fellow prisoner John Bright who was also convicted of murder. Gallows had been constructed for the two in the new Miami jail yard. Kelly’s last statement said that the devil had “prompted him to the deed” and that he would be going “to meet Jesus.” Black hoods were placed over their heads, and the trap sprung on the gallows. Both men were declared dead after being cut down from their ropes.

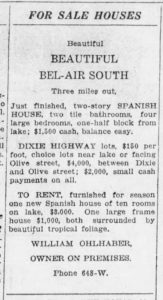

This should logically be the “end of the story,” but many interesting facts remain about the Hone case. Mary mortgaged the house and 20-acre pineapple farm to James Olmstead on December 30, 1904 for $3,000. Olmstead then sold the mortgage to George G. Currie only a year later for $5,000; Mary paid off the mortgage in 1907. In 1923, Currie sold the property to William Ohlhaber, a well-known Chicago architect. Ohlhaber wanted the property to park his yacht, according to family members. Ohlhaber subdivided the property to become Bel-Air, one of the “Roaring Twenties” developments in what was then called South Palm Beach.

Mary continued to live in West Palm Beach, living in a house at the northeast corner of Olive Street and Evernia. In 1919, she applied for a passport to visit her ailing mother in England.

She sailed back to England from New York on the Cunard Line, never to return to West Palm Beach. George Currie visited Mary while on a tour of England and found her well, back in her childhood town. Mary never remarried, and passed away in 1946.

The big storms of 1926 and 1928 and the subsequent Great Depression left Ohlhaber’s Bel-Air subdivision with dozens of unsold lots. In 1947, Max Brombacher, a Henry Flagler employee, bought the Hone house and surrounding property. The house remains in the family hands today, and is considered by most historians to be the oldest house in West Palm Beach (portions of a log cabin built by Elbridge Gale are said to be a part of a house in Northwood, but the house is not in its original location). It is one of the few remaining structures that Charles C. Haight built in West Palm Beach that is still standing.

Richard Hone’s resting place has also seen its share of news over the years. Hone was buried in Lakeside Cemetery, which was at one-time a private cemetery owned by the Lake Worth Pioneers Association. The Association deeded the cemetery to the city of West Palm Beach in 1920 to become Pioneer Park. Most of the burials were moved free-of-charge by the city across the street to Woodlawn Cemetery. Most – but not all. Art collector Ralph Norton proposed building an art museum and school on Pioneer Park, and the city agreed. As part of the agreement, the Lake Worth Pioneer Association holds their annual picnic on the grounds of the Norton Museum. How many burials remain under the Norton is a question that never will be answered. A plaque that once hung by the Norton entrance listed 40 names, but with no mention as to why these 40 names were inscribed. There among them is Richard Hone and two of his children. In the 1920s, the widening of Olive Street revealed many burials that had been forgotten.

In a 1985 discovery, a Norton Museum employee entered a crawlspace under the auditorium in the building and found several forgotten headstones. Most prominent among those was the headstone of Richard Hone, thus inscribed from Job 3:17 “There the wicked cease from troubling and the weary are at rest.” This again stirred up the controversy on the fact that the Norton Museum was built on hallowed ground. At the current time, the whereabouts of the headstone are unknown.

The Hone house and its survival, and the rediscovery of Richard’s headstone, ensured that his story would not be lost to history. The old newspapers accessible through the Internet, and genealogical records, helped to finally crack this case.

May Richard Hone rest in eternal paradise.

I absolutely love the history and intrigue of this story. Thank you for your diligence in reporting the facts.